Wireless spectrum is the range of frequencies used for commercial wireless communications by Mobile Network Operators. It is a finite resource that needs to be allocated and licensed to different parties. As such, there is a typical cost associated with acquiring spectrum outside of public bands. Governments often auction off spectrum licenses to the highest bidder, and the price can be significant, especially for the most desirable spectrum bands with large bandwidth and lower frequencies. The cost of spectrum varies depending on factors such as its capacity, coverage, and demand, with some auctions reaching billions of dollars. The major operators in the United States spent over $100 billion for the 5G spectrum, excluding mergers and acquisitions, to acquire additional spectrum.

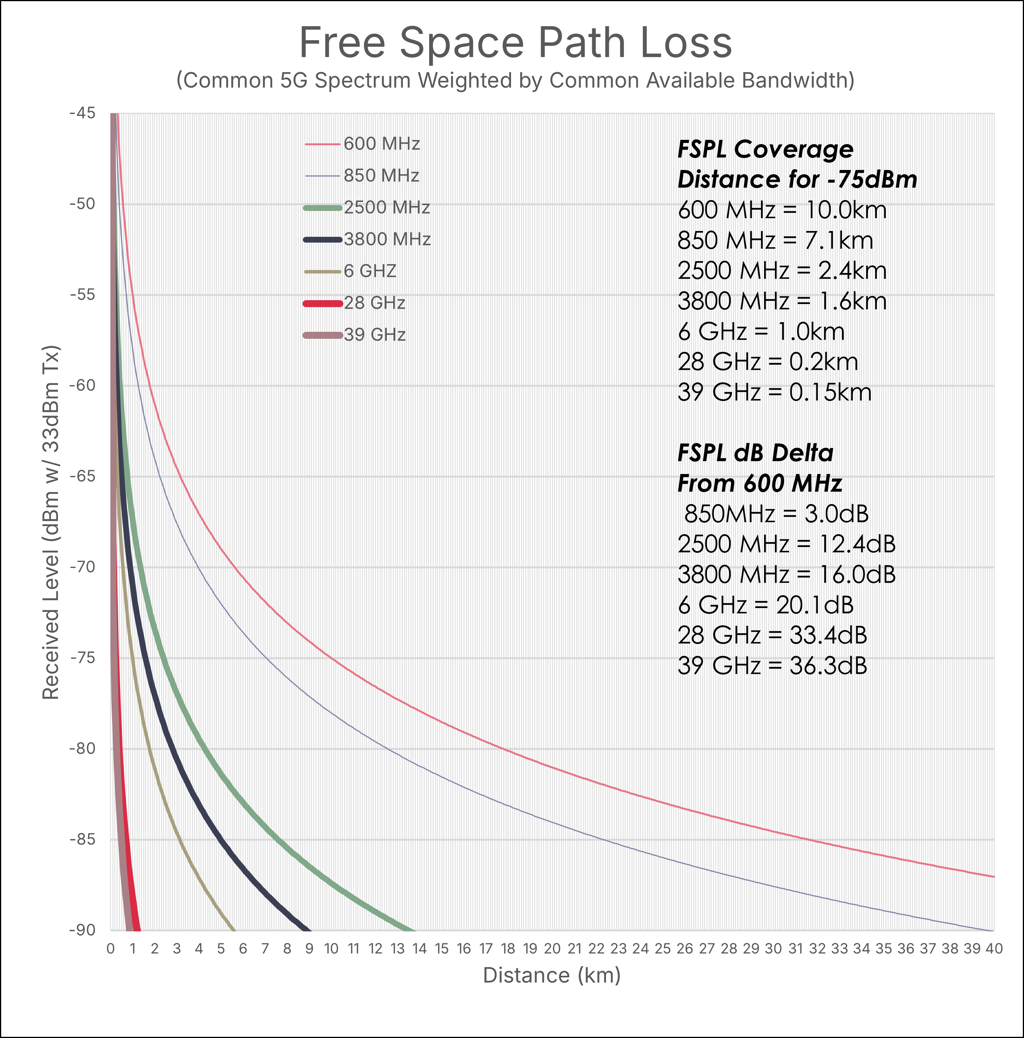

Spectrum bands have different values in terms of their technical characteristics and potential use cases. Low-frequency bands, such as those below 1 GHz, can propagate over longer distances and penetrate buildings and other obstacles better than higher-frequency bands, making them suitable for comprehensive area coverage and rural deployments. On the other hand, high-frequency bands, such as those above 6 GHz, offer greater capacity but have shorter range and poorer penetration. These higher-frequency bands are valuable for dense urban areas and support high-bandwidth applications, such as streaming video.

Spectrum bandwidth enables innovative services for mobile network operators and other industries. The more spectrum a network operator has in MHz, the more data it can transmit simultaneously, leading to faster and more reliable connections. This capacity supports bandwidth-intensive applications, such as streaming video, gaming, and cloud services. Additionally, spectrum bandwidth is crucial for enabling 5G technologies with higher data rates and lower latency compared to previous generations. Beyond mobile network operators, spectrum is also utilized by industries such as aviation, satellite communications, and wireless internet service providers, enabling them to provide critical services and connect remote areas.

While spectrum allocation is often treated as a regulatory milestone, the objective complexity emerges in day-to-day operations. Spectrum usage is inherently dynamic—fluctuating with user demand, environmental interference, and evolving service types. Managing this volatility requires real-time orchestration across multiple layers: from radio access networks (RAN) to core systems and edge deployments. Technologies like dynamic spectrum sharing (DSS) and carrier aggregation offer flexibility, but they also introduce new layers of coordination and conflict resolution. That requires a constant balance between throughput, latency, and interference mitigation while ensuring fairness across services and geographies.

As wireless demand intensifies, operators try to extract maximum value from finite spectrum resources. One key strategy is spectrum refarming, which involves repurposing legacy frequency bands—often used for 2G or 3G—to support modern technologies like LTE and 5G. This transition not only improves spectral efficiency but also enables broader coverage and faster data rates without requiring new spectrum acquisitions. For example, refarming the 900 MHz band from GSM to LTE allows operators to deliver high-speed services using existing infrastructure.

Complementing refarming is carrier aggregation (CA), a technique that combines multiple frequency blocks—either within the same band or across different bands—into a single, wider channel. This aggregation enhances peak throughput, balances coverage and capacity, and improves the user experience in dense environments. 5G and LTE-Advanced networks routinely deploy CA to stitch together fragmented spectrum holdings, enabling gigabit-class speeds and seamless mobility across heterogeneous bands.

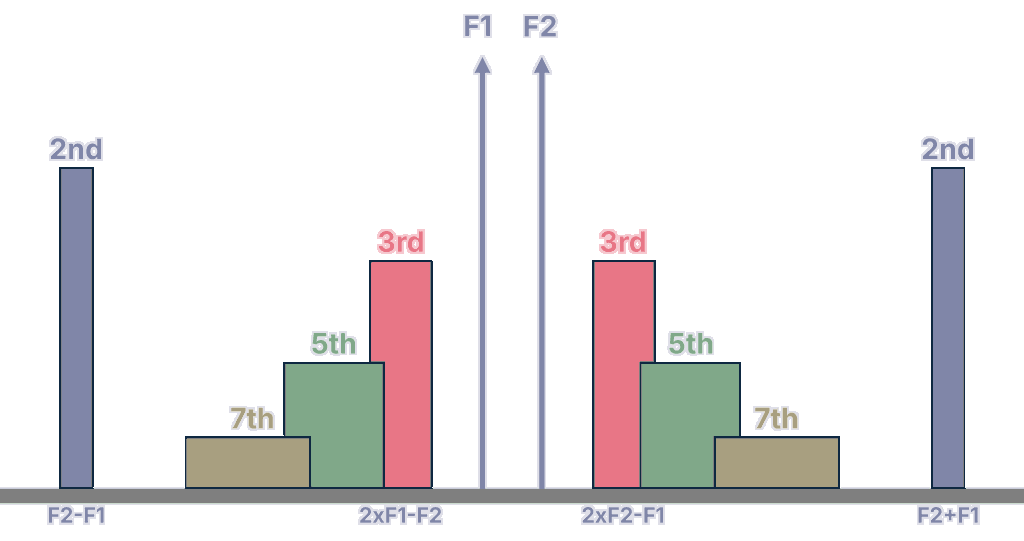

However, high-frequency systems are increasingly vulnerable to Passive Intermodulation (PIM)—a form of interference caused by nonlinear interactions in passive components, such as connectors, cables, and antennas. PIM generates spurious signals that can fall within the receiver’s band, degrading uplink sensitivity and overall network performance. This is especially critical in SHF and EHF deployments, where even minor imperfections can compromise signal integrity. Mitigation requires rigorous installation practices, PIM-rated hardware, and proactive site audits.

Together, these techniques—refarming, aggregation, and interference mitigation—form the backbone of intelligent spectrum management. They enable operators to deliver robust, high-capacity services while navigating the constraints of regulatory allocation and physical infrastructure. As networks evolve toward 6G and beyond, mastering these tools will be essential for sustaining performance and innovation.